Fundamental of Virtual Memory

Contents

- What and Why?

- Simple Allocation Strategy

- External Fragmentation

- Memory Paging

- Demand Paging

- Virtual Memory Layout

- Stack Allocation

- Heap Allocation

- Memory Mapping

What and Why?

Have you ever wondered why computers need main memory (RAM) when they already have disk storage? The answer lies in access speed. While disk storage is permanent, it is much slower than main memory. RAM sacrifices volatility for speed—data is lost when the power is off, but access times are much faster. As a result, the CPU can only access data from main memory, not disk storage.

CPUs come with built-in registers, which are even faster than main memory. So why do we need main memory at all? It’s because registers are limited in number and size. Imagine a function that needs to work with a thousand variables—there’s no way to fit all of them into registers. And what if you need to store large data structures like arrays or structs? Registers simply don’t have the capacity. That’s where main memory comes in—it provides the space needed to handle larger and more complex data.

Main memory is a large array of bytes, ranging in size from hundreds of thousands to billions. Each byte has its own address. For a program to be executed, it must be mapped to absolute addresses and loaded into memory. Once loaded, a process—an active execution of a program—accesses program instructions, reads data from and writes data to memory by using these absolute addresses. In the same way, for the CPU to process data from disk, those data must first be transferred to main memory by CPU-generated I/O calls.

Simple Allocation Strategy

Typically, there are multiple processes running on a computer, each with their own memory space allocated in main memory. It’s the responsibility of the operating system to allocate memory for each process, ensuring that they don’t interfere with each other. One of the simplest methods for allocating memory is to assign processes to a variably sized contiguous block of memory in memory, where each block may contain exactly one process.

|

|---|

| Contiguous memory block allocation strategy 1 |

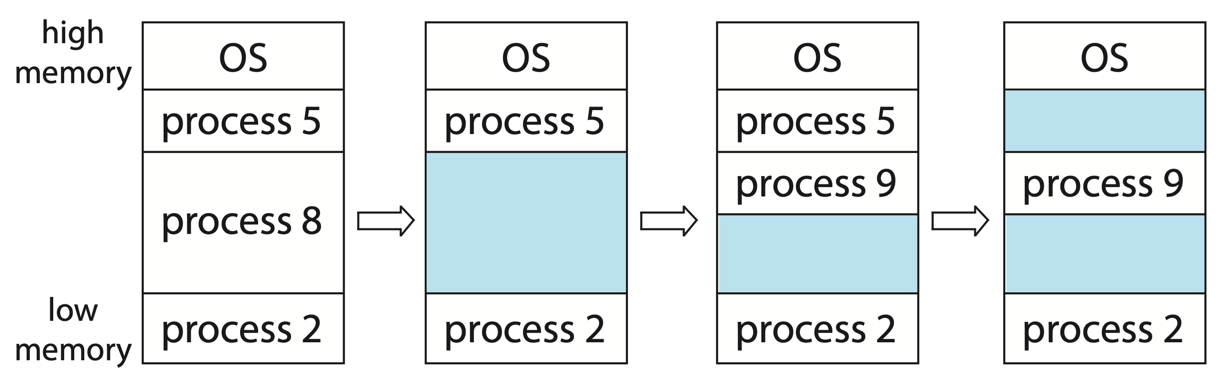

When processes are created, the operating system takes into account the memory requirements of each process and the amount of available memory space to allocate a sufficient partition for it. After allocation, the process is loaded into memory and starts its execution. Once the process is finished, the operating system reclaims the memory block, making it available for other processes. If there is not enough room for an incoming process, the operating system may need to swap out some processes to disk to free up memory space. Alternatively, we can place such processes into a wait queue. When memory is later released, the operating system checks the wait queue to determine if it will satisfy the memory demands of a waiting process.

During allocation, the operating system must look for a sufficiently large contiguous block of memory for the process. There are many algorithms to do this, such as first-fit, best-fit, and worst-fit. First-fit searches for the first block that is large enough and stops searching once it finds one. Best-fit searches the entire memory space and finds the smallest block that is large enough. Worst-fit searches the entire memory space and finds the largest block that is large enough. First-fit and Best-fit perform better than Worst-fit in time and storage use. First-fit is usually faster, though storage efficiency is similar between the two.

External Fragmentation

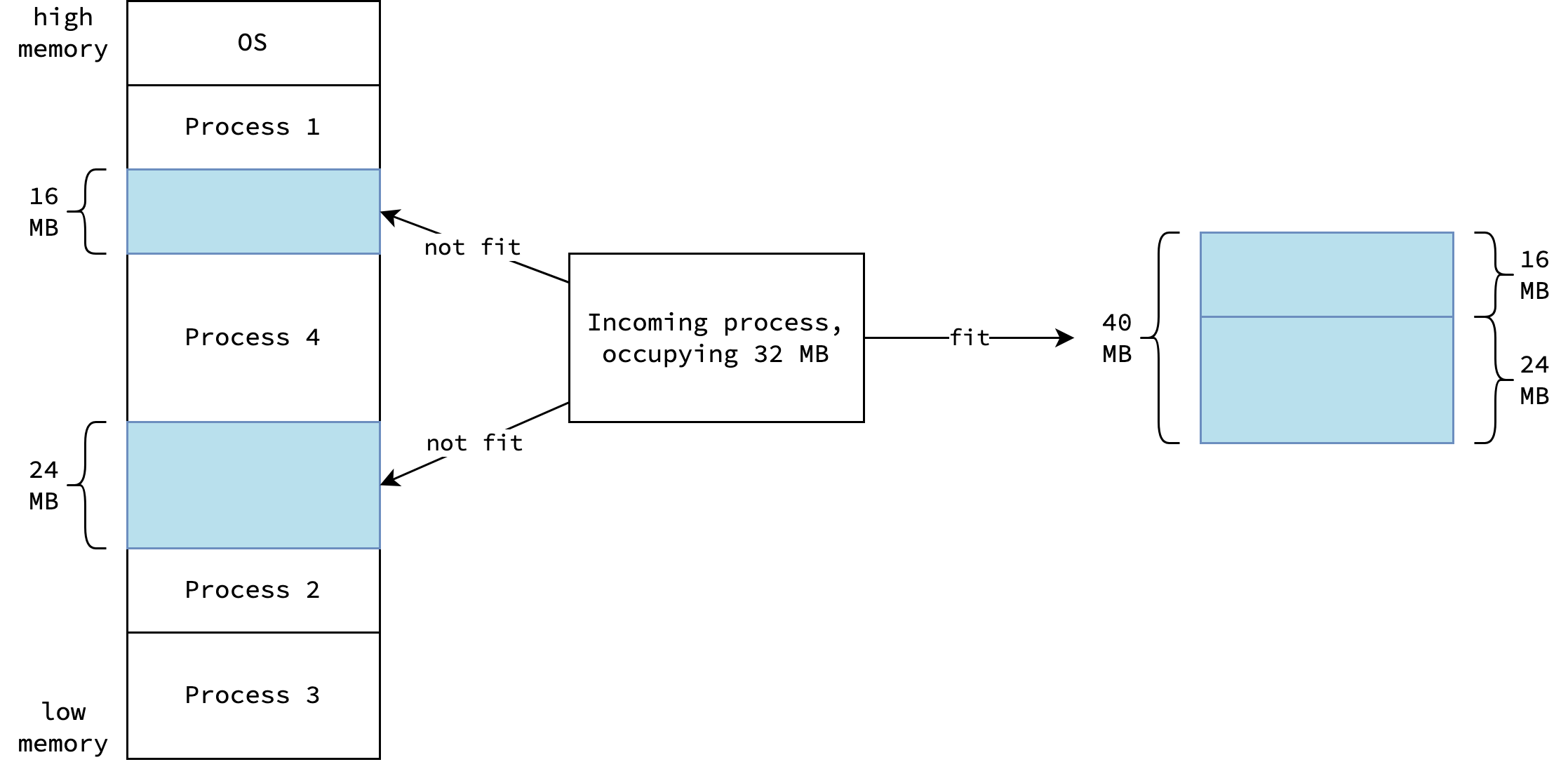

Unfortunately, this simple allocation strategy can lead to external fragmentation. External fragmentation occurs when there is enough total memory to satisfy a request, but the available spaces are not contiguous. This type of fragmentation can become a serious problem. In the worst case, there can be a small block of free memory between every two allocated processes. If all these scattered fragments were combined into a single large block, the system might be able to run several more processes.

|

|---|

| External fragmentation with contiguous memory block allocation strategy |

In reality, the maximum memory space required by a process is not known at the time of allocation. This is because processes may perform dynamic memory allocation based on user input or other factors. If the allocated memory is not enough, the operating system may need to pause the process, search for a sufficient memory block, and migrate the process to a larger memory block. This approach could lead to critical performance issues, thus not realistic.

Memory Paging

In practice, operating systems use a more sophisticated memory allocation strategy called paging to avoid external fragmentation. Paging divides the main memory into fixed-size blocks called frames. Rather than a contiguous block of memory for each process, the operating system allocates multiple frames that can be scattered throughout the main memory.

When mentioning paging, we need to talk about physical memory and virtual memory (or logical memory). Physical memory refers to the main memory installed in the computer, while virtual memory is an abstraction that operating systems use to manage process memory. Processes can only access virtual memory, and the operating system takes care of mapping virtual memory to physical memory. While the process’s physical memory could be non-contiguous, from the perspective of each process, it has its own isolated virtual memory space, appearing as a contiguous block.

🧑💻 To demonstrate the concept of virtual memory, you can try running this Go program, getting the address for later comparison, opening other programs, and then running the program again.

package main func main() { x := 0 println(&x) }You can see that even though there are new processes coming in, the address of the variable remains the same. That’s because the variable is allocated at the same address in the process’s virtual memory space.

The virtual memory is divided into fix-sized blocks called pages, which have the same size as the frames in physical memory. By separating virtual memory from physical memory and with the help of techniques such as demand paging (explained below), a process can access up to 18.4 million TB of memory on a 64-bit architecture, or up to 4 GB on a 32-bit architecture, even if the actual physical memory is much smaller, such as 512 MB.

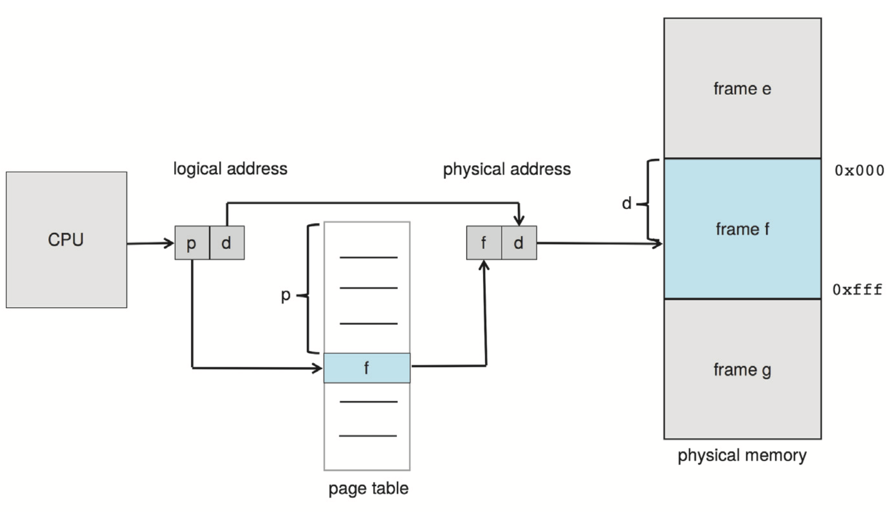

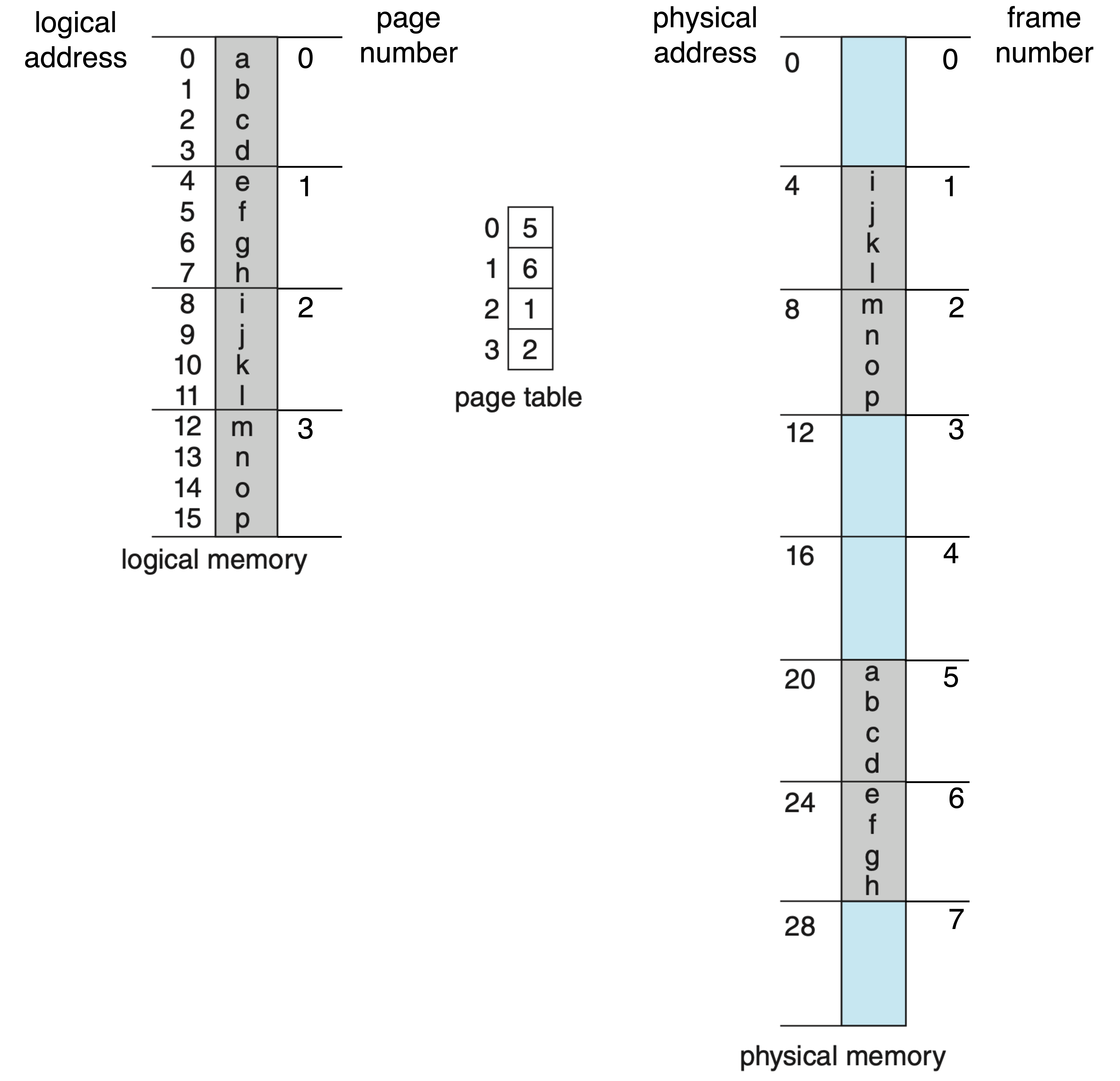

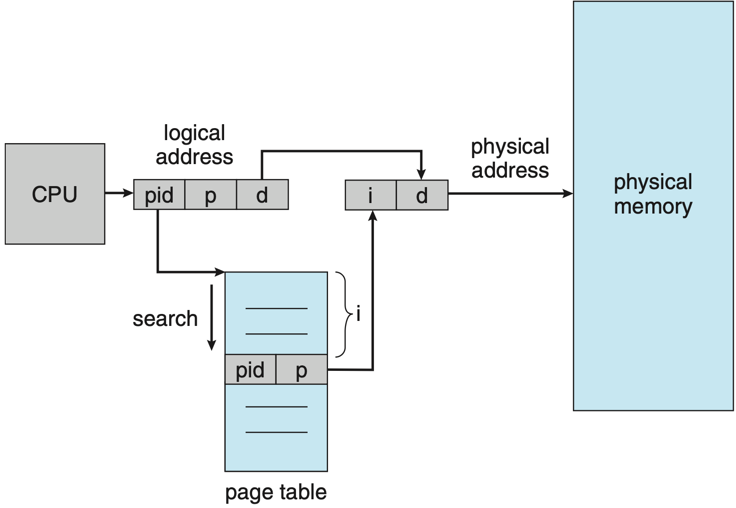

Each page has a page number p, and each frame has a frame number f. Each address has an offset d to identify the specific location within the page or frame. p and f live in the high bits of the address, while d lives in the low bits. The mapping between virtual pages and physical frames is maintained in a per process data structure called a page table. In a page table, each entry is indexed by a page number p, and the corresponding value is the frame number f.

|

|---|

| Paging hardware 2 |

In order to obtain the physical address of a virtual one, the following steps are performed:

- The page number p is extracted from the virtual address.

- The page table is accessed to retrieve the corresponding frame number f.

- Replace the page number p with the frame number f in the virtual address.

|

|---|

| Paging model 3 |

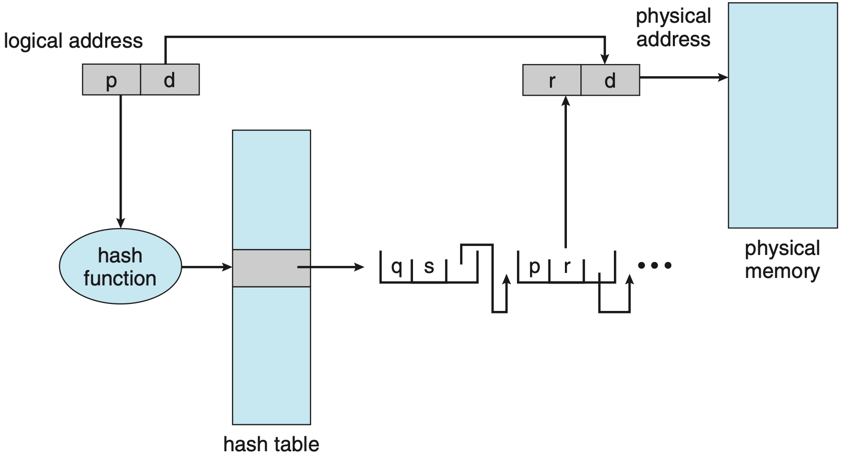

Note that in fact, the structure of a page table is not that simple and it can take several forms to manage memory efficiently. One common approach—used by Linux—is a multi-level page table, where each level contains page tables that map to the next level, eventually leading to the physical frame. Another method is a hashed page table, where a hash function maps virtual page numbers to entries in a hash table that point to physical frames. A third option is an inverted page table, where each entry represents a frame in physical memory and stores the virtual address of the page currently held there, along with information about the owning process.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical page table 4 | Hashed page table 5 | Inverted page table 6 |

Virtual memory allows multiple processes to share files and memory through page sharing. For example, in Chrome, each tab is a separate process but uses the same shared libraries like libc and libssl. Instead of loading separate copies for each tab, the operating system maps the same physical pages into each process, thus reducing memory usage significantly.

Demand Paging

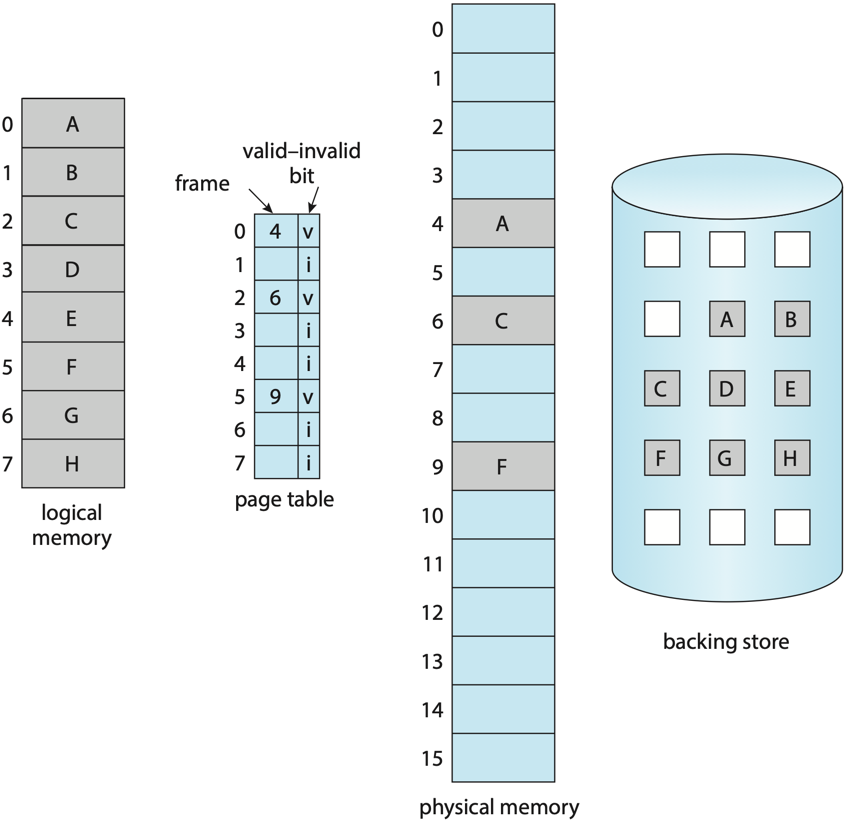

As mentioned earlier, for a program to execute, it must first be loaded into main memory. However, when dealing with large programs, it’s not always necessary to load the entire program at once, only the portion currently needed. Consider an open-world video game: while the entire map may be massive, the player only interacts with and views a small area at any given time, such as a 1 km² region around them. This is where demand paging comes into play. With demand paging, only the required pages of a program are loaded into memory on demand.

|

|---|

| Demand paging 7 |

As a process executes, some of its pages are loaded into memory, while others remain on disk storage (i.e., backing store). To manage this, an additional column called the valid-invalid bit is included in the page table to indicate the status of each page. If the bit is set to valid (v), it means the page is both legal (i.e. belonging to the process’s logical address space) and currently loaded in memory. If the bit is invalid, the page is either outside the process’s logical address space (illegal) or it is a valid page that currently resides on disk.

When a process tries to access a page whose valid-invalid bit is set to invalid (i), a page fault occurs, causing a trap to the operating system. The operating system then follows these steps to handle the page fault:

- It checks the process’s internal table to determine whether the memory reference is valid.

- If the address is invalid (i.e., not part of the process’s logical address space), the process is terminated.

- If the address is valid but the page is not currently in memory, the page is paged in.

- The operating system locates a free frame in physical memory.

- It instructs the disk to read the required page into the newly allocated frame.

- Once complete, the process’s internal table and page table are updated to reflect the presence of the page.

- The process then resumes execution from the instruction that caused the page fault.

In Linux, two key memory metrics are Resident Set Size (RSS) and Virtual Size (VSZ).

RSS represents the amount of physical memory a process is currently using, including shared memory but excluding swapped-out pages.

VSZ, on the other hand, represents the total virtual memory allocated to a process, including shared libraries plus the entire reserved address space, regardless of whether it is currently in physical memory or swapped out.

Also, VSZ includes memory allocated but not yet used by the process, such as memory reserved through mmap or malloc that has not been accessed, which is not included in RSS.

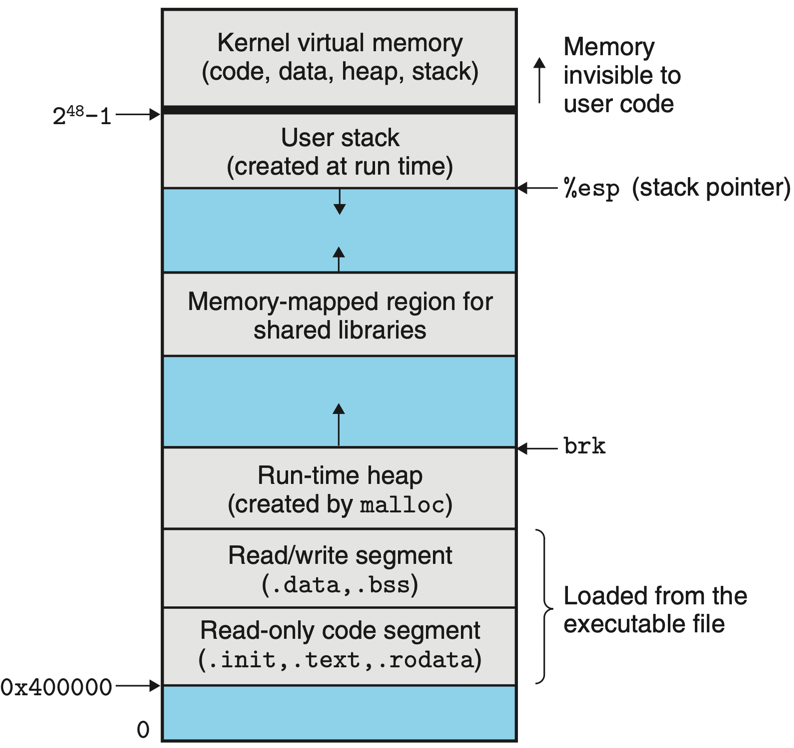

Virtual Memory Layout

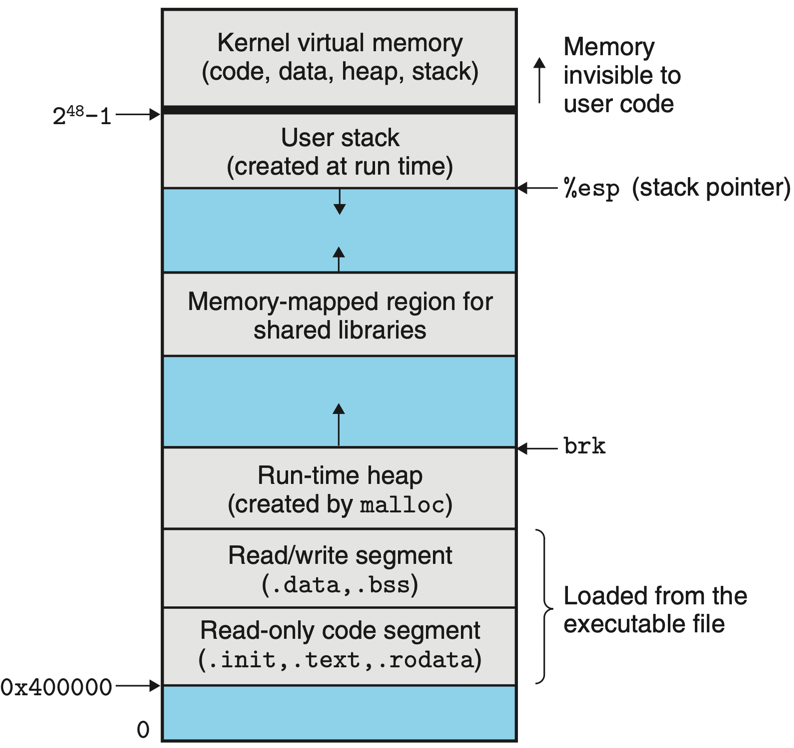

Although virtual memory abstraction frees user-space programmers from managing physical memory directly, challenges still arise during memory allocation. Developers must consider issues such as where to allocate memory, whether a given address is valid, and whether it conflicts with reserved regions like the code segment. To address these issues, operating systems introduce the concept of virtual memory layout. From a process’s perspective, the virtual address layout appears as illustrated below, with addresses growing upward.

|

|---|

| Virtual memory layout of an x86-64 Linux process 8 |

The virtual memory layout is divided into several segments:

- Kernel virtual memory space: Reserved for the kernel and is not accessible to user-space processes.

- (User) Stack: Holds the stack frames of the process’s main thread and grows downward.

- Memory mapped regions: Memory allocated by

mmapfor shared memory, file or anonymous mapping. - Heap: Memory allocated by the process for dynamic memory allocation, which grows upward.

- Initialized data segment (

.data): Contains global and static variables that are initialized by the program. - Uninitialized data segment (

.bss): Contains program’s uninitialized global and static variables. - Read-only code segment: Contains the executable code of the program, which is typically read-only.

Note that these segments are merely pages within the process’s virtual address space.

Stack Allocation

Every process has a stack, a memory segment that tracks the local variables and function calls at some point in time. It’s a data structure that grows downward as functions are called and local variables are allocated, shrinking upward as functions return. When a function is called, a new stack frame is created on the stack, which contains the function’s local variables, parameters, and return address. When the function returns, its stack frame is popped off the stack, deallocating all variables within that stack frame.

| Visualization of how process stack grows and shrinks as program executes 9 |

Every thread has its own stack. Since a process can have multiple threads, there may be multiple stacks within a process.

When we refer to the “process stack”, we typically mean the stack of the main thread.

When a thread is created, it is assigned with a stack that is separate from the main thread’s stack.

Because each thread has an isolated stack, stack allocations do not require synchronization.

If a new thread is created using the pthread_create system call, the kernel by default automatically selects a suitable memory region for the stack.

Alternatively, we can manually specify the starting address of the stack using the pthread_attr_setstack system call.

This behavior also applies to threads created using the clone system call.

The size of the stack is fixed at the time of thread creation, and it cannot be dynamically resized.

The default size of the stack is determined by the RLIMIT_STACK resource limit.

The default value of RLIMIT_STACK is typically 2 MB on most architectures, or 4 MB on POWER and Sparc-64.

While RLIMIT_STACK is global, if we want to set the stack size for a specific thread, we can use pthread_attr_setstacksize to allow for a larger stack if that thread allocates large automatic variables or makes nested function calls of great depth (perhaps because of recursion).

In order to keep track of the top of the stack, the CPU uses a special register called the stack pointer.

Depending on the architecture, it may be called RSP on x86-64, ESP on x86, or SP on ARM.

Before a thread starts executing, the stack pointer is initialized to point to the top of the stack.

As the stack is pre-allocated in thread creation, allocating a variable on the stack is simply moving the stack pointer down, which is a very fast operation.

Loading a variable from the stack is also fast, as it only requires reading the value at the address pointed to by the stack pointer.

There is also another special register called the base pointer (or frame pointer), which points to the start of the current stack frame. It’s used to provide a stable reference point for accessing local variables as well as function parameters. The stack deallocation is done by simply setting the stack pointer back to the base pointer, which is fast.

Since stack allocation is determined at compile time, it is the compiler’s responsibility to calculate the size of all variables and generate the corresponding assembly code to allocate them on the stack.

The compiler also emits instructions to deallocate the stack frame when the function returns.

For example, MOVD is used to store a variable onto the stack, while ADD is used to increase the stack pointer thus deallocate the stack frame.

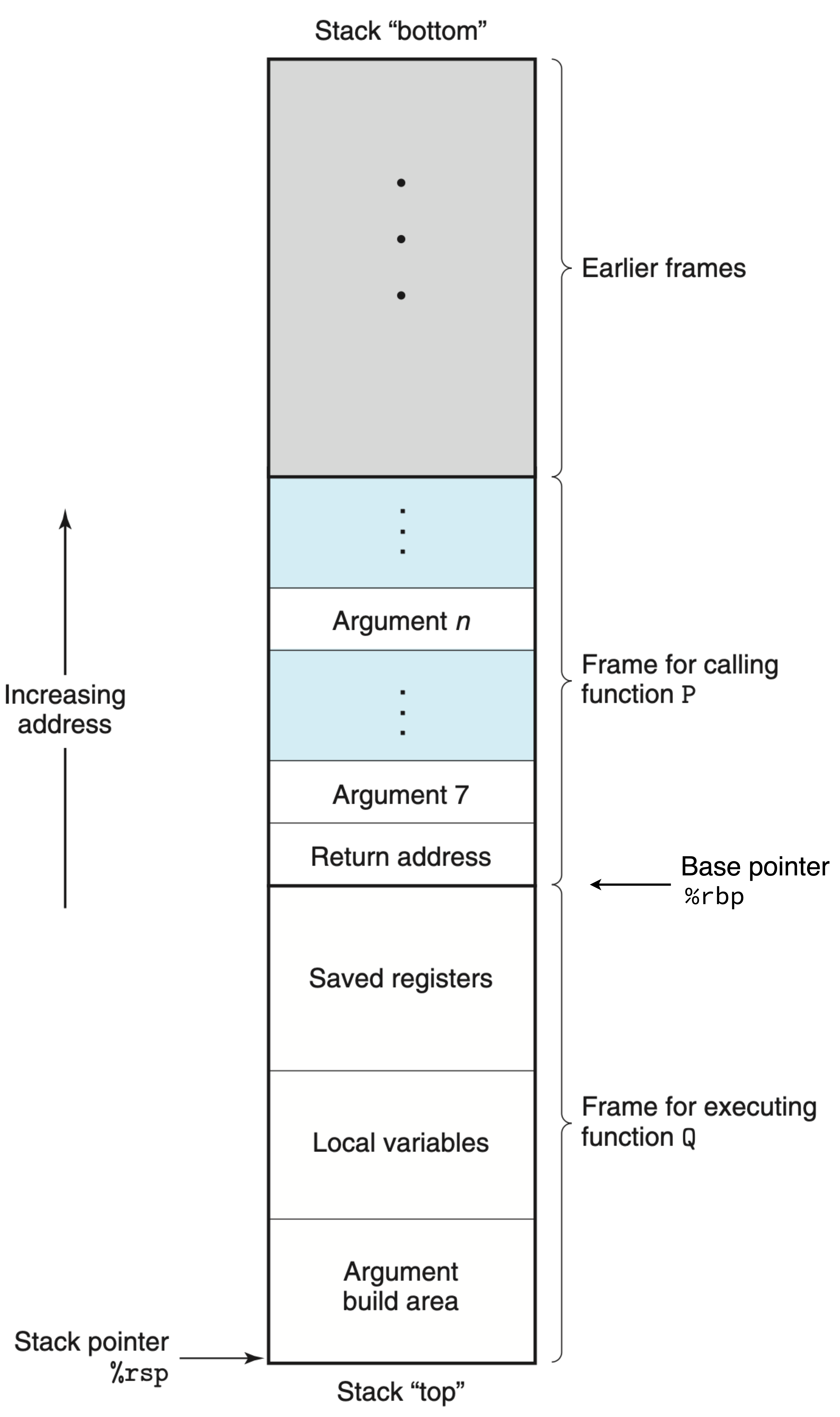

|

|---|

| General stack frame 10 |

The figure above illustrates a general stack frame layout for a scenario in which function P calls function Q.

The frame for the currently executing procedure is always at the top of the stack.

The base pointer (%rbp) marks the start of the current stack frame, while the stack pointer (%rsp) points to the top of the stack.

During P’s execution, it may allocate space on the stack by increasing the stack pointer to store local variables.

When P calls Q, it pushes the return address onto the stack, which tells the program where to resume execution in P after Q returns.

This return address is considered part of P’s stack frame, as it holds state relevant to P.

At this point, P may also save register values and prepare arguments for the called procedure.

When control transfers to Q, the base pointer %rbp no longer points to P’s stack frame; instead, it is updated to point to the start of Q’s frame.

Q then deallocates its own stack frame by decreasing the stack pointer upon returning.

Not every variable should be allocated on the stack due to the following reasons.

Since stack allocation is determined at compile time, if a variable’s size is not known at this time, it can’t be allocated on the stack.

Additionally, if a variable is local to function F but still referenced by another function when F returns, allocating this variable on the stack causes invalid address access.

In such case, we need to allocate the variable on the heap instead.

Heap Allocation

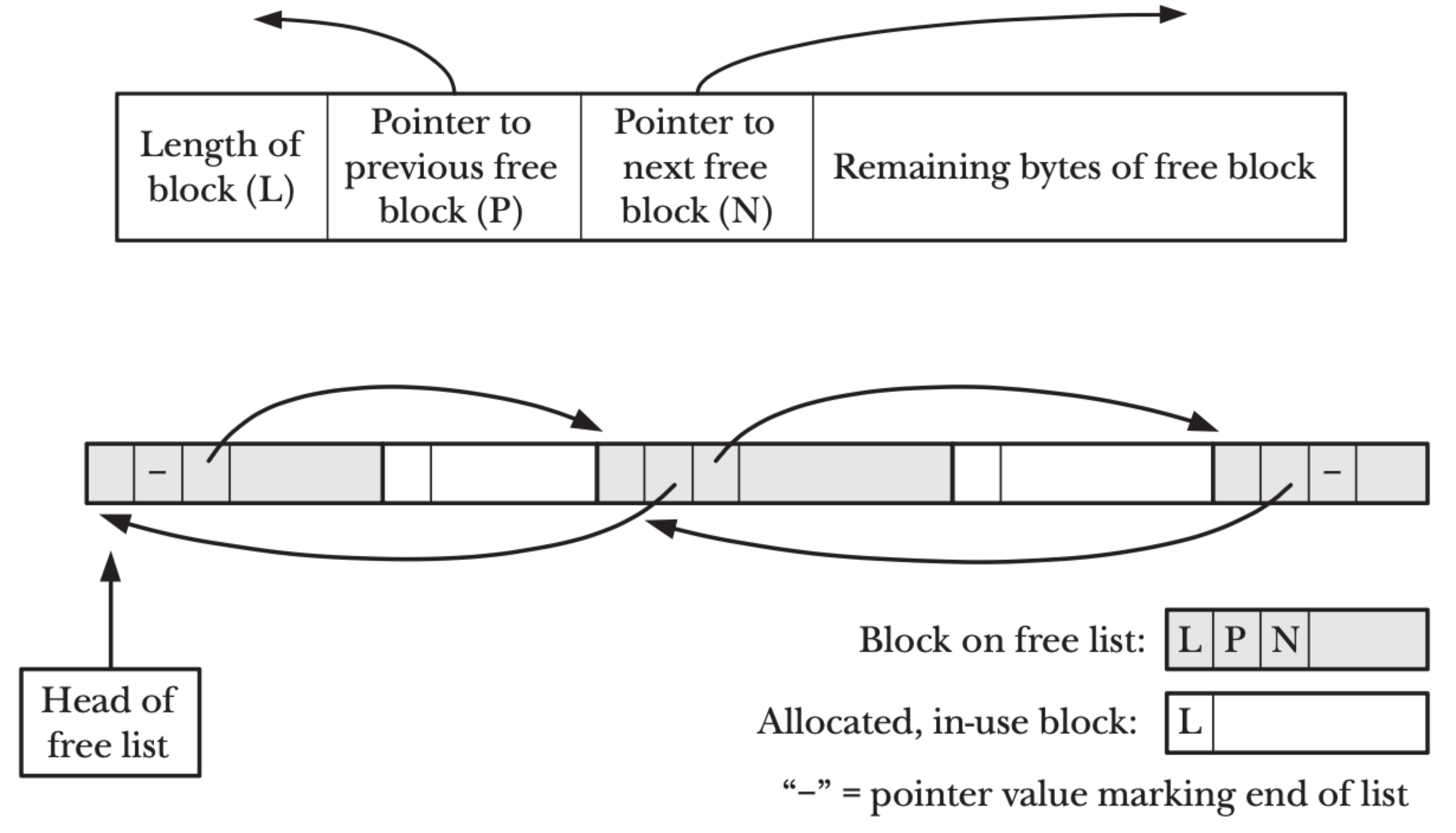

Allocating variables on the heap means finding a free memory block in the heap segment or resizing the heap if there is no such memory block available. The current limit of the heap is referred to as the program break or abbreviated as brk, as depicted in the below figure.

|

|---|

| The position of program break in virtual memory layout |

Resizing the heap is just simple as telling the kernel to adjust its idea of where the process’s program break is. After the program break is increased, the program may access any address in the newly allocated area, but no physical memory pages are allocated yet. The kernel automatically allocates new physical pages on the first attempt by the process to access addresses in those pages. Once the virtual memory for the heap is expanded, the process can choose any memory block to hold the value of the variable.

Linux provides the brk system call to change the position of the program break and the sbrk system call for how much to increase the program break.

While programmers usually care about a variable’s size when allocating it, brk and sbrk are rarely used and malloc is used in Linux instead.

malloc first scans the list of memory blocks previously released by free in order to find one whose size is larger than or equal to its requirements.

Different strategies may be employed for this scan, depending on the implementation; for example, First-fit or Best-fit.

If the block is exactly the right size, then it is returned to the caller.

If it is larger, then it is split, so that a block of the correct size is returned to the caller and a smaller free block is left on the free list.

If no block on the free list is large enough, then malloc calls sbrk to allocate more memory.

To reduce the number of calls to sbrk, rather than allocating the exact amount of memory required, malloc increases the program break in larger units, putting the excess memory onto the free list.

The figure below depicts how malloc manages memory blocks in the heap, which is a one-dimensional array of memory addresses.

Each memory block, apart from the actual space used for storing value of variables, also stores its metadata such as the length of the block and pointers to the previous and next blocks in the free list.

This metadata allows malloc and free to function properly.

|

|---|

| Free list visualization11 |

As the heap is shared across threads, to avoid corruption in multithreaded applications, mutexes are used internally to protect the memory-management data structures employed by these functions. In a multithreaded application in which threads simultaneously allocate and free memory, there could be contention for these mutexes. Therefore, heap allocation is less efficient than stack allocation.

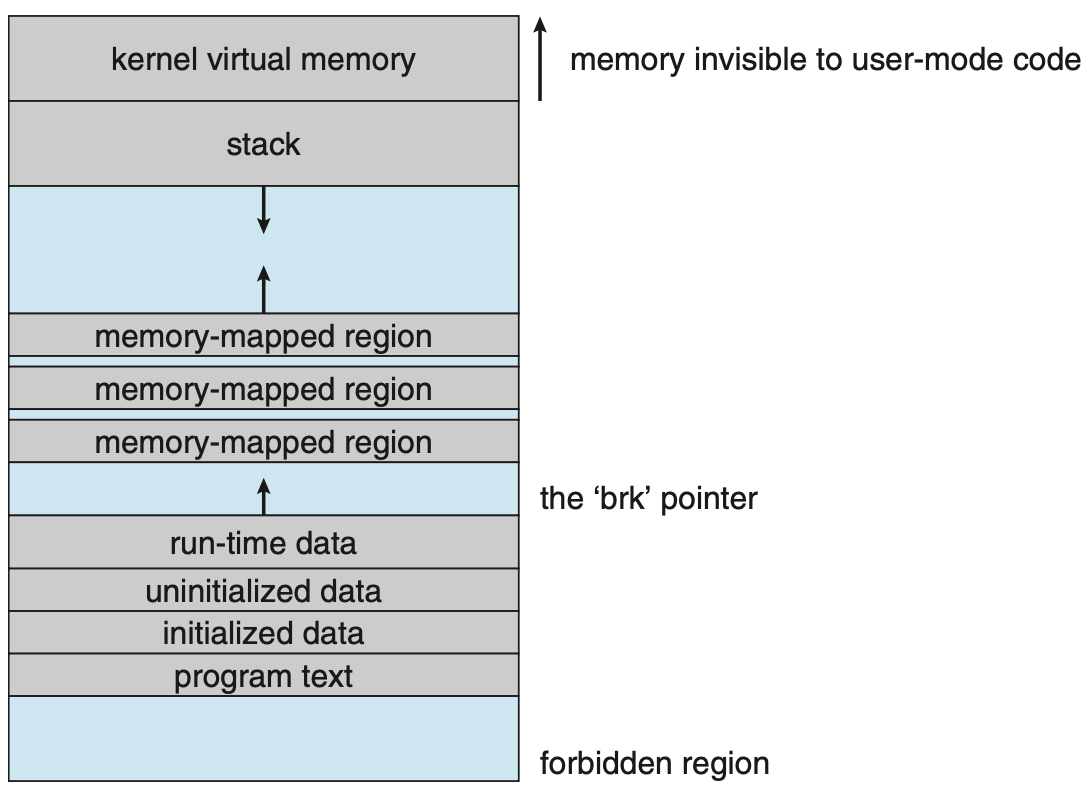

Memory Mapping

As depicted in the virtual memory layout figure below, apart from the heap and the stack, there is also a memory segment called memory mapped regions. There are two types of memory mapping: file mapping and anonymous mapping. A file-mapping maps a region of a file directly into the calling process’s virtual memory, allowing its contents to be accessed by operations on the bytes in the corresponding memory region. An anonymous mapping doesn’t have a corresponding file; instead, the pages of the mapping are initialized to 0. Another way of thinking of an anonymous mapping is that it is a mapping of a virtual file whose contents are always initialized with zeros.

|

|---|

| Memory layout for ELF programs 12 |

A memory mapped region can be private (aka. copy-on-write) or shared. By private, it means that the memory region is only accessible by the process that created it. Whenever a process attempts to modify the contents of a page, the kernel first creates a new, separate copy of that page for the process and adjusts the process’s page tables. Conversely, if the memory mapped region is shared, then all processes that share the same memory mapped region can see the changes made by any of them.

Demand paging also works for memory mapping. When a user process’s address space is expanded, kernel does not immediately allocate any physical memory for these new virtual addresses. Instead, the kernel implements demand paging, where a page will only be allocated from physical memory and mapped to the address space when the user process tries to write to that new virtual memory address13. The read accesses will result in creation of a page table entry that references a special physical page filled with zeroes14.

Since anonymous memory mappings are not backed by a file and are always zero-initialized, they are ideal for programs that implement their own memory allocation strategies—such as Go—rather than relying on the operating system’s default allocators like malloc and free.

This allows greater control over memory management, enabling features like custom allocators or garbage collection tailored to the runtime’s needs.

Linux provides the mmap system call to create a new memory mapping in the virtual address space of a process.

The parameter most worth mentioning is addr, which specifies the preferred starting address of the mapping.

If addr is set to NULL, the kernel automatically selects a suitable address.

If a non-NULL value is provided, the kernel treats it as a hint and attempts to place the mapping near that address, rounding as needed to the nearest page boundary.

In all cases, the kernel ensures that the chosen address does not conflict with existing mappings.

References

- Core Dumped. Why is the Stack So Fast?

- Michael Kerrisk. The Linux Programming Interface.

- Abraham Silberschatz, Peter B. Galvin, Greg Gagne. Operating System Concepts.